Beef is more than just a staple protein it is a complex culinary landscape defined by genetics, muscle anatomy, and the science of heat. Whether you are selecting a holiday roast or a Tuesday night steak, understanding the nuances of beef from USDA grading to the Maillard reaction is essential for any home cook or meat enthusiast.

1. Understanding Quality: USDA Grading and Marbling

The quality of beef is primarily determined by marbling (intramuscular fat) and the age of the animal. In the United States, the USDA provides a grading system that serves as a shorthand for flavor and tenderness:

- USDA Prime: The highest grade, featuring abundant marbling. Usually reserved for high-end steakhouses, these cuts are ideal for dry-heat cooking.

- USDA Choice: High quality but with less marbling than Prime. Choice cuts from the loin and rib are excellent for grilling.

- USDA Select: Leaner and typically less tender. These cuts benefit from marination or slow-cooking to break down muscle fibers.

Beyond grading, consider the animal’s diet. Grass-fed beef tends to be leaner with a complex, “earthy” flavor profile and higher Omega-3 content, while grain-fed beef offers the buttery richness and consistent marbling many consumers prefer.

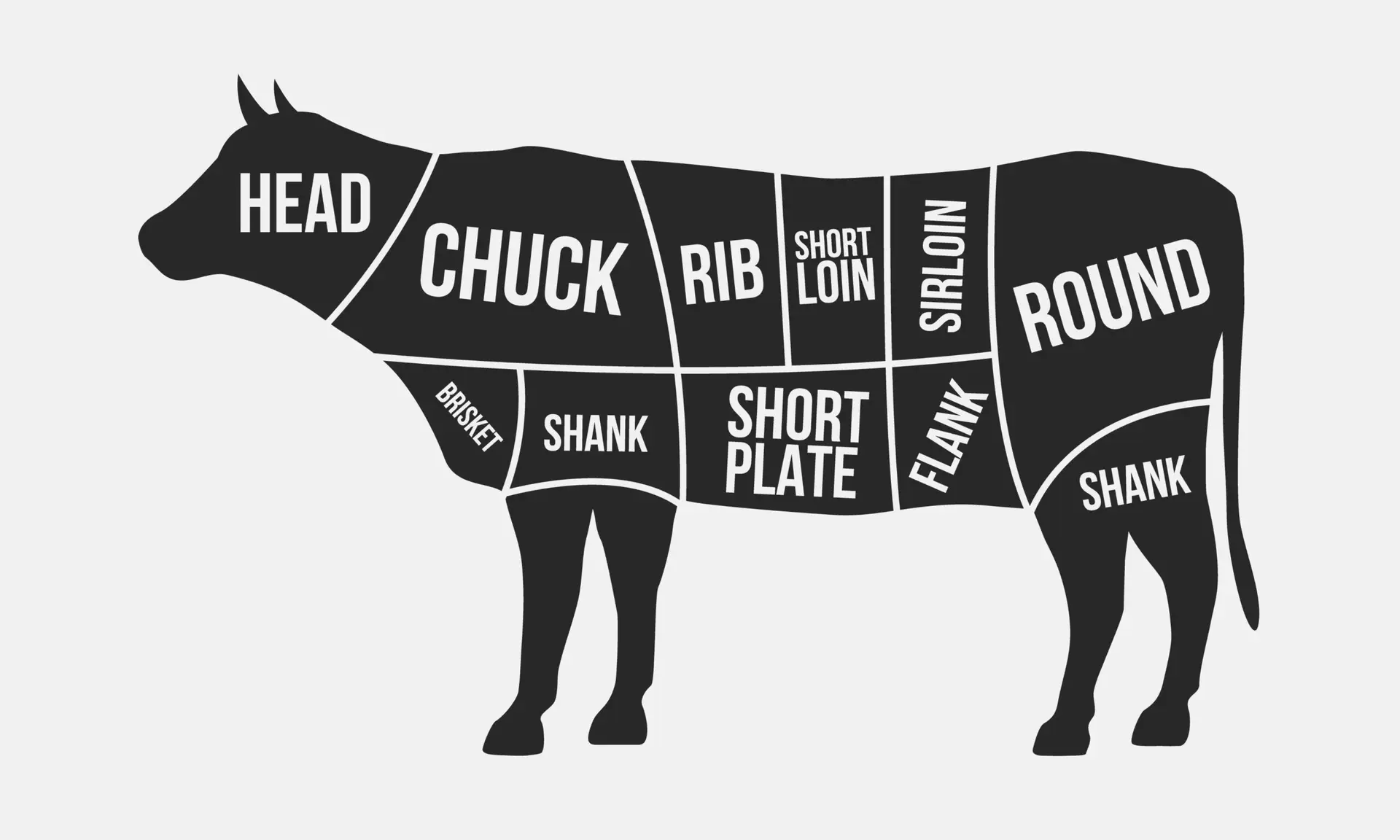

2. Navigating the Primal Cuts

To master beef, you must understand where it comes from on the animal. A cow is divided into “primal cuts,” each with distinct textures and cooking requirements.

The Forequarter (Workhorse Cuts)

- Chuck: Located in the shoulder, this area does a lot of work. It is rich in collagen and connective tissue, making it the gold standard for pot roasts and stews.

- Brisket: Taken from the breast, this tough cut requires “low and slow” heat to transform tough fibers into melt-in-your-mouth BBQ.

- Rib: Home to the Ribeye and Prime Rib. These are high-fat, high-flavor sections that require minimal seasoning.

The Hindquarter (Premium Steaks)

- Loin: This is where you find the T-bone, Porterhouse, and Filet Mignon. These muscles don’t do much heavy lifting, resulting in extreme tenderness.

- Round: The hind leg area. These cuts (Top Round, Eye of Round) are lean and best sliced thin for roast beef or jerky.

3. The Science of the Perfect Sear

The difference between a grey, boiled-looking steak and a crusty, mahogany-colored masterpiece is the Maillard reaction. This chemical reaction occurs between amino acids and reducing sugars when exposed to high heat (above 140°C or 285°F).

Pro-Tip: The Reverse Sear

For thick-cut steaks (1.5 inches or more), use the Reverse Sear method:

- Slow Heat: Bake the beef in a low oven ($120^{\circ}\text{C}$) until the internal temperature reaches $46^{\circ}\text{C}$.

- The Finish: Flash-sear the meat in a ripping-hot cast-iron skillet for 60 seconds per side. This ensures an even edge-to-edge pink center with a professional crust.

4. Temperature and Resting: The Final Steps

The most common mistake in preparing beef is cutting it too soon. When beef cooks, muscle fibers contract and push juices toward the center. Resting the meat for 5–10 minutes allows those fibers to relax and reabsorb the moisture.

| Desired Doneness | Internal Temp (Finish) | Texture/Description |

| Rare | $52^{\circ}\text{C}$ ($125^{\circ}\text{F}$) | Cool red center |

| Medium-Rare | $57^{\circ}\text{C}$ ($135^{\circ}\text{F}$) | Warm red center (The Gold Standard) |

| Medium | $63^{\circ}\text{C}$ ($145^{\circ}\text{F}$) | Warm pink center |

| Well Done | $71^{\circ}\text{C}$+ ($160^{\circ}\text{F}$+) | Little to no pink, firm texture |

Conclusion

Beef is a versatile protein that rewards knowledge. By choosing the right cut for your cooking method whether it’s a collagen-rich chuck for a winter braise or a marbled Ribeye for the grill you ensure a superior dining experience. Always prioritize sourcing, mind your internal temperatures, and never skip the rest.